Enlightenment Now, 8 Years On

Steven Pinker's Enlightenment Now argues that Enlightenment principles like reason and science advance human progress. The book is full of historical data and charts that illustrate the many ways in which incredible progress has already been made in recent decades and centuries.

Recently, I was wondering how things have changed since its publication in February 2018. Here's an update on some key progress indicators.

Continued Positive Trends

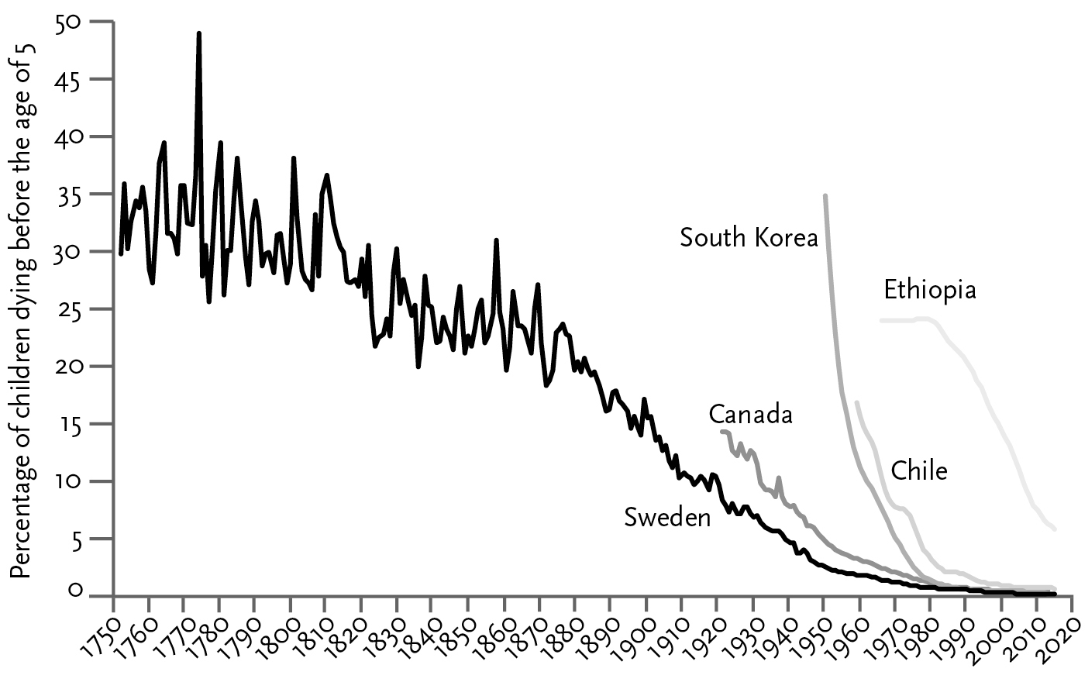

Many of the metrics discussed in the book have continued on their positive trend and were largely unaffected by other world events in the past 8 years. Here is Figure 5-2 from the book, which illustrates the trends in childhood mortality for a selection of countries over time.

And here is an update that includes the next ten years of data. Global childhood mortality has continued to fall steadily through 2023.

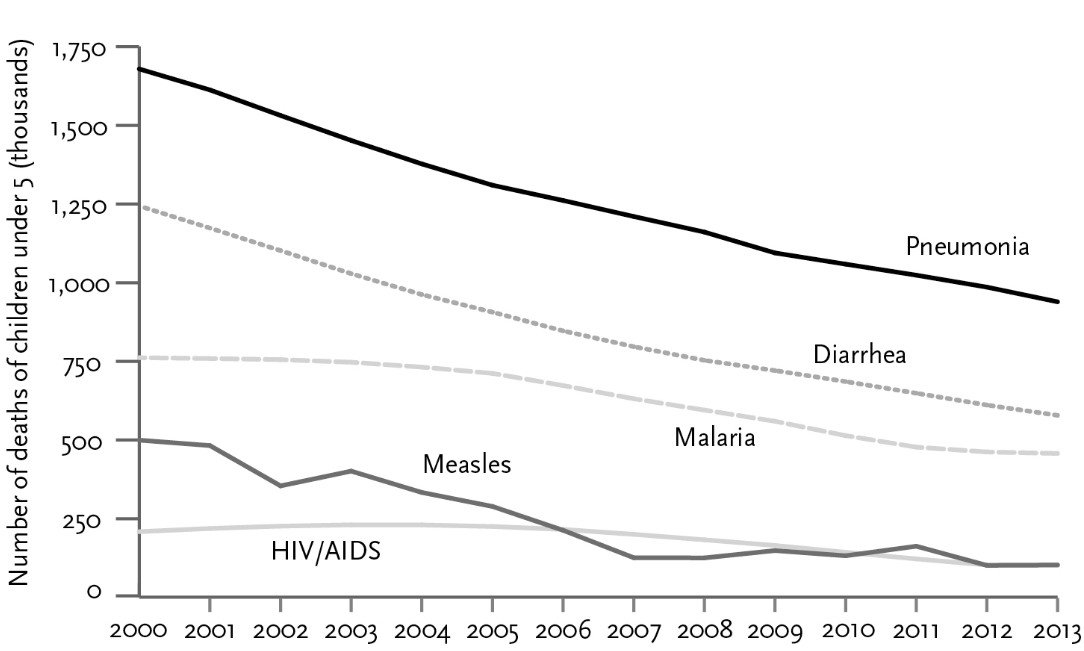

Childhood deaths from the most lethal infectious diseases has also continued to fall. Here is Figure 6-1 from the book.

And here is the updated version which shows a continued downward slope. There was a small increase in malaria deaths in 2020 and 2021 but the deaths for each of these years was still below the 2015 count.

Other metrics that had continued positive trends include literacy rates, years of schooling, daily supply of calories per person, and the number of countries protecting key women's rights and LGBT+ rights. Annual working hours continued to fall or stay relatively flat for the US and Western Europe.

Many metrics experienced minor setbacks during the COVID-19 pandemic but have rebounded in recent years. Life expectancy was on a relatively smooth incline for for decades. It dropped slightly during the pandemic. But as vaccinations rose the death rate fell, and life expectancy has since resumed its previous trajectory with global life expectancy in 2023 (73.2 years) exceeding that of 2019 (72.6 years).

Global median income took a small downturn in 2020, then jumped back up above 2019 levels in 2021 and has been on the increase ever since.

One of the most striking stories of progress from the book was the reduction in extreme poverty between 1990 and 2010:

In 2000 the United Nations laid out eight Millennium Development Goals, their starting lines backdated to 1990. At the time, cynical observers of that underperforming organization dismissed the targets as aspirational boilerplate. Cut the global poverty rate in half, lifting a billion people out of poverty, in twenty-five years? Yeah, yeah. But the world reached the goal five years ahead of schedule. Development experts are still rubbing their eyes. Deaton writes, “This is perhaps the most important fact about wellbeing in the world since World War II.”

The share of population living in extreme poverty bumped up briefly during the pandemic, but has since begun to decline again. In 2022 the global rate was back to the same level it was at in 2019 (10.8%) and has been decreasing every year since. The rate that was halved between 1990 and 2010 was halved again between 2010 and 2023.

In 2020, the US experienced the largest one-year increase in homicide deaths. In the following year, the global rate rose slightly. Then a few years later the rates declined rapidly. By 2023, the global rate had dropped back below pre-pandemic levels and the US rate was headed in that direction.

The number of maternal deaths followed a similar pattern as many of these other measures. There was an increase in the number of deaths in 2021 but previous trends were restored in 2022 and 2023.

GDP per capita dipped in 2020 but then continued to climb.

US Motor vehicle traffic fatalities also spiked during the pandemic, rising by 7.3% in 2020 and 10.8% in 2021. But they have been falling every year since and are heading toward pre-pandemic levels.

Negative Developments

Progress isn't inevitable. As Pinker notes:

... progress is not an escalator that inexorably raises the well-being of every human everywhere all the time. That would be magic, and progress is an outcome not of magic but of problem-solving. Problems are inevitable, and at times particular sectors of humanity have suffered terrible setbacks.

There have been several setbacks in recent years.

The share of people who are undernourished started to rise even prior to COVID and remained "stubbornly high" in the early 2020s according to the WHO. The problem wasn't as bad as it had been back in 2000, but it had regressed to "levels of undernourishment comparable to those in 2008-2009." In 2025, hunger fell globally but continued to rise in Africa.

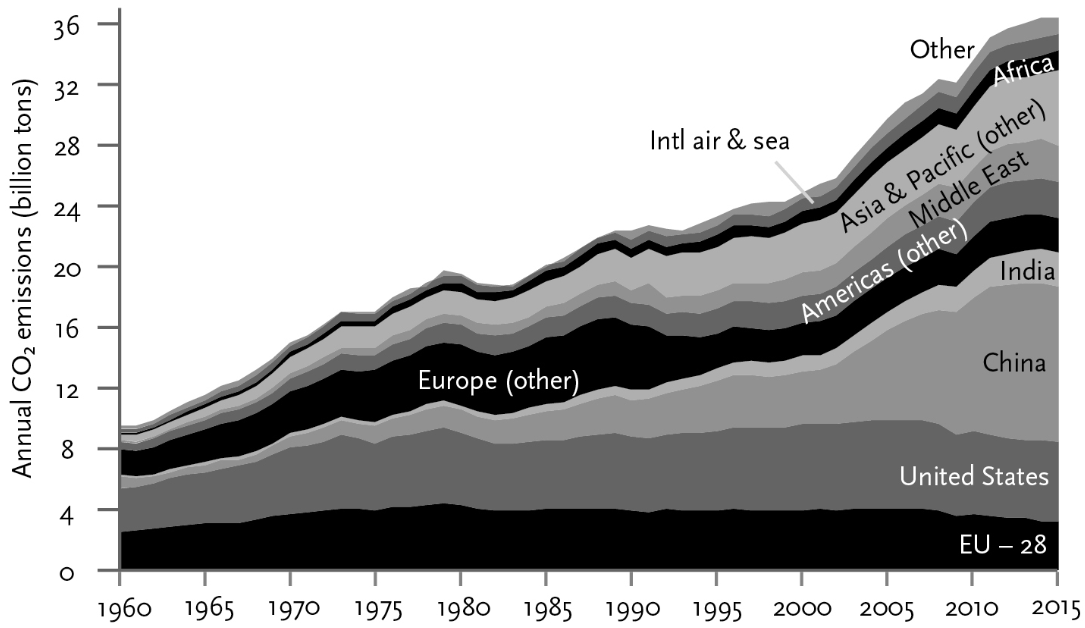

When Enlightenment Now was written, CO₂ emissions were showing some promise. The overall trend was upward but global emissions had "plateaued from 2014 to 2015 and declined among the top three emitters, namely China, the European Union, and the United States." This can be seen in Figure 10-8 from the book.

The good news is that emissions have continued to fall for the US and EU since then. The bad news is that the plateau that China was experiencing in the mid-2010s was short-lived and their emissions have increased every year since 2016.

Deaths in state-based conflicts, which were already on the rise in the 2010s due to the Syrian civil war, have continued to increase. The bulk of the deaths in recent years have been from the Tigray war in Ethiopia and the Russo-Ukrainian war.

Another recent negative change in the data is an increase in the number of people living in autocracies. The recent major shift is due to V-Dem's reclassifying India as an "electoral autocracy" in 2017.

The negative shift is less pronounced when viewing the countries that are democracies and autocracies.

Final Thoughts

While reviewing these numbers, I was surprised and heartened by how many indicators had remained on a positive track or were quickly bouncing back so soon after the world had just endured a global pandemic, supply chain shocks, and high inflation.

Though the negative setbacks are discouraging, many of them hinge on the activity of only a few countries. Hopefully these areas will begin to look better in the coming years. Progress is possible.