EV Adoption

Electric vehicle adoption has been growing for years. But EVs still make up only a fraction of new car purchases.

In their book Abundance, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson argue that one step toward building a cleaner economy is to electrify everything. And to do that, we need to persuade people to choose clean alternatives when the time comes to replace their car or other large appliances:

People need to want these alternatives. That means the alternatives need to be excellent, which in many cases they now are. Electric cars accelerate faster and run quieter than cars powered by combustion engines. Induction stoves boil water in a fraction of the time it takes those little licks of fire. Because these advantages are not universally known—and because new technologies are more expensive than mature ones—subsidies need to be generous, and advertising needs to be everywhere.

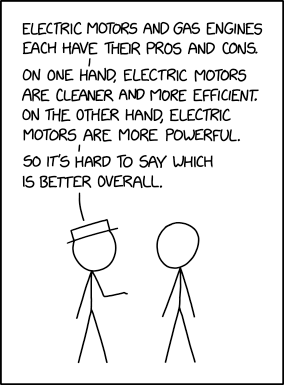

A similar argument was made in this xkcd comic:

It's not hard to find opinion pieces that explain why EVs are an "obvious upgrade" because they are "quieter, cleaner, more efficient and easier to maintain".

But the idea that people aren't buying EVs because of a failure to communicate how quiet, clean, and fast they are is silly.

The main reasons people are reluctant to purchase EVs have been reported on for years and remain consistent:

- Charging stations are limited

- Charging time takes longer than pumping gas

- Range tends to be low

- Upfront costs are high

These reasons are practical and rational. They're about time and money and whether a car can meet one's driving needs. Apartment dwellers may not have consistent access to a charging location at home. Drivers with longer commutes as well as those from single-car households are less likely to purchase EVs.

It's often argued that even though EVs are expensive to purchase they save money in the long run because energy costs are low and EVs require less maintenance (e.g. no oil changes). But their economic advantage also depends on the cost of gas, electricity prices, public charging costs, and depreciation. Head-to-head comparisons reveal that sometimes a hybrid is still the cheaper option, even when generous EV tax credits were available.

Range is impacted by towing and by cold temperature. As Consumer Reports notes:

We found that cold weather saps about 25 percent of range when cruising at 70 mph compared with the same conditions in mild weather. In the past, we found that short trips in the cold with frequent stops and the need to reheat the cabin saps 50 percent of the range.

These may not be huge concerns for drivers with short commutes, but they are serious impediments to full adoption. In How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, Bill Gates (who loves his electric vehicle) writes about the challenges to long-haul trucking:

According to a 2017 study by two mechanical engineers at Carnegie Mellon University, an electric cargo truck capable of going 600 miles on a single charge would need so many batteries that it would have to carry 25 percent less cargo. And a truck with a 900-mile range is out of the question: It would need so many batteries that it could hardly carry any cargo at all.

Keep in mind that a typical truck running on diesel can go more than 1,000 miles without refueling. So to electrify America's fleet of trucks, freight companies would have to shift to vehicles that carry less cargo, stop to recharge more often, spend hours of time recharging, and somehow travel long stretches of highway where there are no recharging stations. It's just not going to happen anytime soon. Although electricity is a good option when you need to cover short distances, it's not a practical solution for heavy, long-haul trucks.

This is also why electric aircraft won't be replacing fossil-fuel-powered jets in the near future. The energy density of batteries is too low.

I've been driving a hybrid for over a decade now and it's great. When I bought it, everything was an improvement over my previous car—lower emissions, better fuel economy, longer range, shorter fueling time, and more cargo space. It's kind of a bummer that a transition to an all-electric car wouldn't be a slam dunk in the same way. It's not an obvious upgrade.

- "Number of new cars sold, by type, United States". Our World in Data. Accessed February 2026.

- Klein, Ezra, & Thompson, Derek (2025). Abundance. New York: Avid Reader Press, An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC. pp. 68, 101-102, 106-108.

- Monroe, Randall. "Electric vs Gas". xkcd. June 19, 2024.

- Sher, Hebron. "Electric vehicles are simply better. Here’s the proof.". The Hill. July 23, 2025.

- Morgan, Kate. "Three big reasons Americans haven’t rapidly adopted EVs". BBC. November 9, 2023.

- Threewitt, Cherise. "Reasons People Don't Buy Electric Cars (and Why They're Wrong)". U.S. News & World Report. February 26, 2025.

- "EV Purchase Consideration Ebbs While Charging Concerns Continue to Grow, JD Power Finds". JD Power. May 16, 2024.

- Barry, Keith. "Will an Electric Car Save You Money?". Consumer Reports. February 16, 2023.

- Yantakosol, Matt. "How Is EV Driving Range Impacted by Towing?". JD Power. April 26, 2024.

- Bartlett, Jeff S., & Shenhar, Gabe. "CR Tests Show Electric Car Range Can Fall Far Short of Claims". Consumer Reports. January 17, 2024.

- Gates, Bill (2021). How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. pp. 141-142.